When you read a story that leaves you feeling unsettled, elated, or melancholy, you’ve experienced mood in literature. Literary mood is one of the most powerful tools writers use to connect with readers on an emotional level. Unlike many technical aspects of writing, mood works subtly beneath the surface, coloring our entire reading experience without always drawing attention to itself.

Mood in literature refers to the emotional atmosphere that a text creates and the feelings it evokes in readers. It’s the difference between a story that merely entertains and one that resonates deeply within us long after we’ve turned the final page. Masters of literary mood don’t just tell stories—they create emotional experiences.

Contents

ToggleWhat Is Mood in Literature A Deeper Definition

Mood in literature is the emotional response or feeling that a piece of writing evokes in the reader. Unlike many other literary elements that exist primarily within the text itself, mood exists in the relationship between the text and its audience. It’s not just what the author puts on the page—it’s what the reader experiences as a result.

Literary mood can be:

- Sustained throughout an entire work

- Shifted gradually as the narrative progresses

- Changed suddenly for dramatic effect

- Layered with multiple emotional undertones

- Specific to certain scenes or passages

What makes literary mood particularly fascinating is that it’s created through the careful orchestration of multiple elements working in harmony. A writer doesn’t simply state “this scene is scary”—instead, they craft an experience that makes the reader feel fear through carefully selected details, pacing, word choice, and imagery.

The Psychological Impact of Mood

Literary mood operates on both conscious and subconscious levels. Research in cognitive psychology suggests that emotional responses to text can occur before readers have fully processed the content intellectually. This emotional processing happens in the limbic system—the brain’s emotional center—creating genuine physiological responses to fiction: increased heart rate during suspenseful scenes, relaxation during comforting passages, or even tears during moments of profound sadness.

This psychological dimension is why literary mood is so powerful. When authors successfully create a particular mood, they’re not just communicating ideas—they’re triggering emotional experiences that mirror real life, creating a profound sense of connection between reader and text.

Distinguishing Between Related Concepts

Mood vs. Tone in Literature The Critical Difference

One of the most common confusions in literary analysis is the distinction between mood and tone. While closely related and often working in tandem, they represent different aspects of literary expression:

Mood in Literature: The emotional response evoked in the reader Tone in Literature: The author’s attitude toward the subject matter or audience

This distinction becomes clearer through example. Consider this passage from Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities”:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity…”

The tone here is paradoxical and somewhat ironic—Dickens is deliberately presenting contradictory statements to establish complexity. The mood, however, is one of tension and uncertainty, leaving readers feeling a sense of historical vastness and looming conflict.

While tone and mood can align (a sarcastic tone might create an amusing mood), they often diverge. A writer might adopt a detached, clinical tone when describing horrific events, creating a disturbing mood precisely because of this emotional disconnect.

Atmosphere vs. Mood The Environmental Distinction

Another important distinction is between atmosphere and mood:

Mood: The emotional response experienced by the reader Atmosphere: The environmental or situational qualities that contribute to mood

Atmosphere often serves as the foundation upon which mood is built. Gothic novels like “Wuthering Heights” establish an atmospheric foundation—wild moors, isolated mansions, howling winds—that supports the development of their brooding, mysterious moods.

The key difference lies in direction: atmosphere flows from the text toward the reader, while mood is what develops within the reader as a result. A writer might describe an empty playground at twilight (atmosphere) to evoke a sense of wistful nostalgia or eeriness (mood).

Setting vs. Mood Location and Emotion

Setting (the time and place of a story) contributes significantly to mood but isn’t synonymous with it. The same setting can create entirely different moods depending on how it’s presented:

A forest at night might create:

- A mood of wonderment when filled with fireflies and moonlight

- A mood of terror when shadowy and filled with strange sounds

- A mood of serenity when described with gentle breezes and soft animal calls

This demonstrates that mood emerges not just from what setting elements are present, but how they’re portrayed, which details are emphasized, and what associations they trigger.

The Spectrum of Literary Moods

Literary mood encompasses a vast emotional spectrum far beyond simple binaries like “happy” or “sad.” Professional writers work with nuanced variations of emotional states to create precise effects. Here’s an expanded vocabulary of literary moods with examples:

| Mood Category | Specific Mood Variations | Example in Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Joyful | Elated, Whimsical, Carefree, Jubilant | “The Wind in the Willows” by Kenneth Grahame |

| Melancholic | Wistful, Brooding, Elegiac, Bittersweet | “Never Let Me Go” by Kazuo Ishiguro |

| Mysterious | Enigmatic, Cryptic, Suspenseful, Intriguing | “The Name of the Rose” by Umberto Eco |

| Foreboding | Ominous, Menacing, Unsettling, Portentous | “Rebecca” by Daphne du Maurier |

| Peaceful | Tranquil, Serene, Contemplative, Harmonious | “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau |

| Tense | Anxious, Nerve-wracking, Fraught, Agitated | “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy |

| Nostalgic | Reminiscent, Yearning, Sentimental, Longing | “Dandelion Wine” by Ray Bradbury |

| Intimate | Confidential, Vulnerable, Personal, Tender | “Giovanni’s Room” by James Baldwin |

This table demonstrates the richness of emotional territory available to writers. Developing a nuanced vocabulary for describing literary mood helps both writers and readers articulate the specific emotional experiences created by different texts.

Creating Mood in Literature Essential Techniques

Understanding literary mood begins with recognizing the craftwork behind it. Great writers create mood through a deliberate orchestration of multiple elements rather than relying on explicit emotional statements. Let’s explore the fundamental techniques that contribute to mood creation.

Language and Word Choice The Building Blocks of Mood

Words carry emotional associations beyond their dictionary definitions. Compare these descriptions of the same sunset:

- “The sun dissolved into the horizon, painting the clouds in soft pinks and golds that seemed to whisper goodnight to the drowsy world below.”

- “The sun bled into the horizon, staining the clouds with angry reds and sickly yellows that warned of the darkness to come.”

Both describe the same natural phenomenon, but the first creates a peaceful, comforting mood while the second establishes something ominous and foreboding. This emotional impact comes from:

Connotative language: Words like “dissolved,” “painting,” and “whisper” versus “bled,” “staining,” and “warned” carry vastly different emotional associations

Sound patterns: Soft consonants and long vowels often create gentler moods than harsh consonants and short vowels

Imagery types: The sensory details writers choose to emphasize dramatically affect mood

Rhythm and Sentence Structure The Heartbeat of Prose

The rhythm of prose—created through sentence length, structure, and variation—dramatically impacts mood. Consider these patterns:

Short, staccato sentences create urgency, tension, or abruptness:

“He waited. The door opened. A gun appeared. He ran.”

Long, flowing sentences can create contemplative, luxurious, or overwhelming moods:

“The river flowed endlessly toward the horizon, carrying with it the fallen leaves of autumn, the memories of summer days, and the promises of winters yet to come, all moving inexorably toward the waiting sea that had received these offerings for countless millennia before humans ever walked these shores.”

Varied sentence structures can create complex emotional landscapes that shift subtly throughout a passage, guiding the reader through different emotional states.

Imagery and Sensory Details The Sensory Experience

While visual imagery dominates many discussions of literary description, mood often emerges most powerfully through multisensory writing. Each sense has unique emotional potential:

| Sense | Mood Potential | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Visual | Establishes setting and spatial relationships | “The peeling wallpaper curled away from the walls like yellowed fingernails.” |

| Auditory | Creates immediacy and environmental presence | “The floorboards whispered secrets with each cautious step.” |

| Tactile | Generates intimate, physical connection | “The morning air bit at his exposed skin with tiny frozen teeth.” |

| Olfactory | Triggers memory and visceral responses | “The sweet-sick smell of lilies choked the funeral parlor.” |

| Gustatory | Evokes primal satisfaction or disgust | “Each word tasted bitter on her tongue, like unripe persimmon.” |

The most effective mood-building often combines multiple sensory channels, creating an immersive experience that envelops readers completely.

Pacing and Rhythm The Temporal Experience

How quickly or slowly information unfolds significantly impacts mood:

Accelerated pacing (short paragraphs, quick scene transitions, minimal description) creates excitement, urgency, or anxiety

Decelerated pacing (extended descriptions, longer paragraphs, philosophical asides) creates contemplation, dread, or immersion

Rhythmic variations create emotional complexity through contrast

F. Scott Fitzgerald demonstrates masterful pacing control in “The Great Gatsby,” alternating between languorous descriptions of wealth and rapid, dialogue-driven scenes of conflict, creating a mood that mirrors the precarious nature of the characters’ artificial world.

Symbolism and Motifs The Subconscious Layer

Recurring images, objects, colors, and patterns work on a subconscious level to reinforce mood:

- Weather phenomena: Rain, fog, sunshine as emotional correlatives

- Color motifs: Repeated color associations building emotional landscapes

- Natural elements: Water, fire, earth with their psychological associations

- Object symbolism: Items that accumulate emotional significance

In Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” water imagery appears repeatedly—from the crossing of the Ohio River to Sethe’s water breaking—creating a persistent mood that connects birth, death, memory, and rebirth through this elemental symbol.

Mood in Literature Forms

Mood in Poetry Concentrated Emotion

Poetry’s condensed form demands particularly efficient mood creation. Poets rely heavily on:

- Sound devices: Alliteration, assonance, and consonance creating emotional textures

- Line breaks: Controlling the reader’s emotional rhythm through pacing

- White space: Using visual arrangement to create emotional pause and emphasis

- Formal constraints: Using traditional forms to create expected emotional patterns or breaking them for emotional effect

Consider how Emily Dickinson creates an unsettling, almost otherworldly mood in “Because I could not stop for Death” through her unconventional capitalization, hymn-like meter, and the juxtaposition of mundane and eternal elements.

Contemporary poet Ocean Vuong creates intimacy through fragmented lines and sensory immediacy in “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong”:

“Ocean, don’t be afraid.

The end of the road is so far ahead

it is already behind us.

Don’t worry. Your father is only your father

until one of you forgets.”

The direct address, simple language, and paradoxical imagery create a confessional, vulnerable mood that draws readers into a deeply personal emotional space.

Mood in Fiction The Narrative Arc

Fiction writers have the advantage of extended development, allowing mood to:

- Evolve gradually throughout a narrative arc

- Contrast dramatically between scenes or chapters

Reflect character psychology as it changes - Build toward emotional climaxes

Novels often establish a baseline mood in early chapters, then modulate it throughout the story to align with plot developments. Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway” begins with a mood of bustling anticipation that gradually reveals undercurrents of melancholy and disconnection as the characters’ inner lives are exposed.

Mood in Drama The Dynamic Experience

Dramatic works create mood through unique tools:

- Stage directions: Setting environmental conditions for scenes

- Dialogue rhythm: Creating emotional patterns through speech

- Visual spectacle: Using lighting, setting, and movement as mood elements

- Silence: Employing pauses and unspoken tensions

Tennessee Williams’ stage directions in “A Streetcar Named Desire” are famously atmospheric, calling for specific music, lighting, and environmental sounds that establish the sultry, tense mood of New Orleans before any character speaks a word.

Mood in Digital and Interactive Literature New Frontiers

Contemporary digital literature creates mood through:

- Visual design elements: Typography, color schemes, and layout

- Interactive pacing: Reader-controlled progression affecting emotional experience

Multimedia integration: Sound, animation, and visual elements - Branching narratives: Different emotional pathways based on reader choices

Works like Porpentine’s “With Those We Love Alive” ask readers to actually draw symbols on their skin while reading, creating a mood of ritualistic intimacy impossible in traditional formats.

Advanced Mood Techniques in Literature

Dynamic Mood Progression: The Emotional Journey

While amateur writers often establish a single mood and maintain it, sophisticated writing uses mood progressions to create emotional complexity:

- Mood arcs: Emotional journeys that parallel plot arcs

- Mood contrasts: Juxtaposition of different emotional atmospheres

- Mood motifs: Recurring emotional patterns that gain significance

- Mood reversals: Dramatic shifts that recontextualize previous scenes

Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” demonstrates this brilliantly, weaving between magical wonder, familial warmth, political tension, and existential melancholy—sometimes within single paragraphs—creating a multidimensional emotional landscape that mirrors the complex history of Macondo itself.

Mood Dissonance: Creating Emotional Complexity

Some of the most powerful mood effects come from intentional dissonance:

- Comedic elements in tragedy: Creating emotional relief that heightens subsequent darkness

- Disturbing elements in comfortable settings: Undermining security to create unease

- Beautiful descriptions of terrible things: Creating aesthetic-emotional tension

- Mundane reactions to extraordinary events: Highlighting disconnection or alienation

Flannery O’Connor mastered this technique in stories like “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” where polite Southern manners and casual conversation continue even as violence unfolds, creating a uniquely unsettling mood through this dissonance.

Unreliable Narration and Mood Manipulation

Unreliable narrators offer unique opportunities for mood creation:

- Mood inconsistencies that hint at narrator instability

- False mood establishment that’s later revealed as deception

- Mood shifts that reveal evolving mental states

- Reader doubt creating a meta-mood of uncertainty

Kazuo Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day” uses its narrator’s emotional repression to create a profound sense of unacknowledged loss. The butler Stevens establishes a mood of professional pride and propriety, but subtle cracks in his narration reveal the devastating emotional costs of his choices.

Cultural and Historical Dimensions of Mood

Literary mood doesn’t exist in isolation—it connects to broader cultural contexts:

- Historical mood: Capturing the emotional tenor of an era

- Cultural emotional codes: Drawing on shared emotional references

- Political mood: Reflecting collective anxieties or aspirations

- Generational mood: Capturing age-specific emotional experiences

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” creates not just character-specific moods but captures the collective emotional trauma of slavery and its aftermath. The mood emerges from both personal and historical dimensions, creating an emotional experience that connects individual story to cultural memory.

Practical Applications: Crafting Mood in Your Writing

Step-by-Step Mood Development Process

Creating effective mood in writing involves a deliberate process:

- Identify your emotional target: Define precisely what emotional response you want to evoke

- Select appropriate mood elements: Choose settings, imagery, language, and pacing that support your target mood

- Create sensory foundations: Establish multisensory details that build the emotional environment

- Layer mood elements: Combine multiple techniques rather than relying on a single approach

- Test and refine: Get feedback on whether readers experience the intended emotional effect

Common Mood Pitfalls to Avoid

Even experienced writers sometimes struggle with mood creation. Watch for these common issues:

- Mood telling instead of showing: Explicitly stating emotions rather than creating them through experience

- Mood inconsistency: Unintentionally contradictory emotional signals

- Mood oversaturation: Using too many mood techniques at once, creating confusion

- Clichéd mood elements: Relying on overused imagery (dark and stormy night, etc.)

- Forced mood: Trying to create emotions that don’t organically emerge from the story

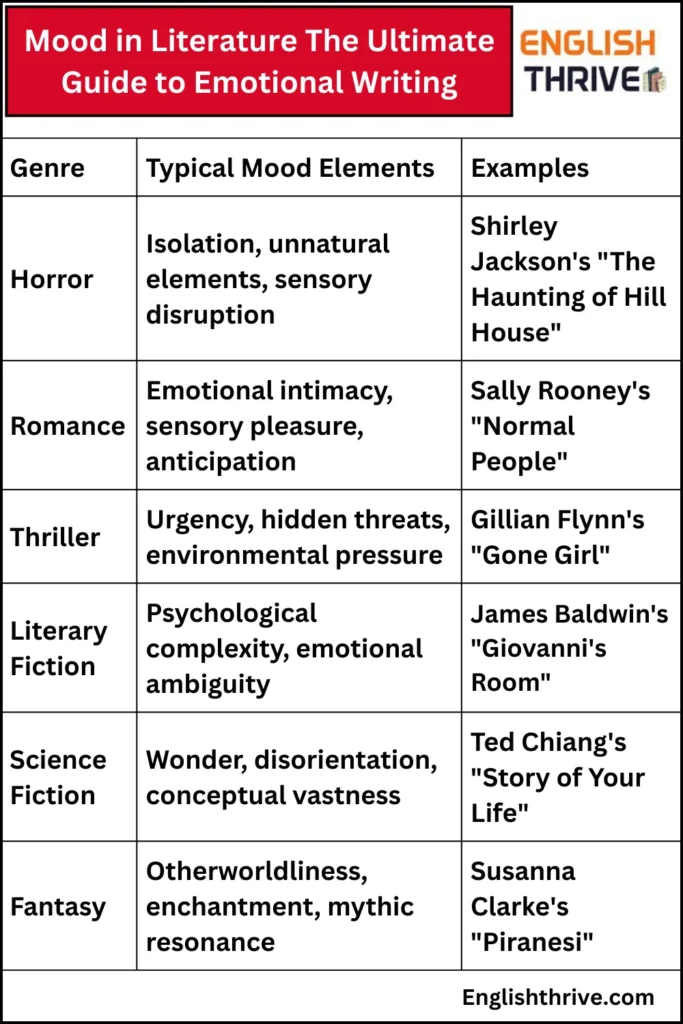

Genre-Specific Mood Considerations

Different genres come with distinct mood expectations and techniques:

| Genre | Typical Mood Elements | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Horror | Isolation, unnatural elements, sensory disruption | Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House” |

| Romance | Emotional intimacy, sensory pleasure, anticipation | Sally Rooney’s “Normal People” |

| Thriller | Urgency, hidden threats, environmental pressure | Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” |

| Literary Fiction | Psychological complexity, emotional ambiguity | James Baldwin’s “Giovanni’s Room” |

| Science Fiction | Wonder, disorientation, conceptual vastness | Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” |

| Fantasy | Otherworldliness, enchantment, mythic resonance | Susanna Clarke’s “Piranesi” |

Each genre has developed specialized mood techniques that writers can study and adapt.

Mood and Reader Psychology: The Emotional Contract

Effective mood creation considers the psychological contract between writer and reader:

- Emotional preparation: Preparing readers for the intended emotional experience

- Emotional consent: Not violating reader expectations without purpose

- Emotional cadence: Providing necessary relief from intense moods

- Emotional resonance: Connecting literary mood to universal human experiences

When writers understand this relationship, they can create profound emotional experiences while maintaining reader trust.

The Neuroscience of Literary Mood

Recent research in cognitive neuroscience has begun to illuminate how literary mood affects readers at a neurological level:

- Mirror neurons activate when reading emotionally charged scenes, creating genuine emotional responses

- Language processing centers connect more deeply to emotional centers when reading mood-rich text

- Memory formation is enhanced for emotionally resonant reading experiences

These findings confirm what writers have intuitively understood: well-crafted literary mood creates real emotional experiences in readers—experiences that may persist long after the book is closed.

FAQs on Mood in Literature

What is the mood in literature?

Mood in literature is the emotional atmosphere or the overall feeling a writer creates for readers. It helps shape how readers emotionally connect to a story—whether they feel happy, scared, calm, or tense.

What is mood and examples?

Mood refers to the emotional effect a piece of writing has on the reader.

Examples include:

A horror story that creates a frightening mood.

A romantic novel that sets a loving or tender mood.

A nature poem that builds a peaceful mood.

What are the 4 types of mood?

The four common types of mood in literature are:

Joyful – evokes happiness or excitement.

Sad – expresses sorrow or melancholy.

Tense – creates suspense or fear.

Peaceful – brings calmness and relaxation.

What best defines mood in literature?

Mood is best defined as the emotional atmosphere that a writer creates to influence how the reader feels. It’s the emotion or vibe that fills the story through setting, tone, and word choice.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Mood

Mood in literature goes far beyond simple atmospheric decoration—it is fundamental to how we experience stories. Through mood, writers create not just intellectual engagement but emotional investment, bringing readers into worlds that feel as real and significant as their own lived experiences.

The most memorable works of literature are often those that create the most powerful moods. From the eerie, gothic atmosphere of Shirley Jackson’s stories to the sunlit nostalgia of Ray Bradbury’s summer tales, from the existential dread of Kafka to the magical wonder of Gabriel García Márquez—these works remain with us because they’ve created emotional experiences that become part of who we are.

As writers, developing our ability to craft mood is not just about mastering technique but about honoring the profound emotional connection between writer and reader—the shared humanity that makes literature not just an art form but a bridge between minds and hearts across time and space.

When we read words that make us feel, we are experiencing one of humanity’s most remarkable achievements: the ability to transmit emotion through language alone. In this way, literary mood isn’t just an element of craft—it’s the very essence of why we write and read at all.